Hieroglyph Read online

CONTENTS

FOREWORD—LAWRENCE M. KRAUSS

PREFACE: INNOVATION STARVATION—NEAL STEPHENSON

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

INTRODUCTION: A BLUEPRINT FOR BETTER DREAMS—ED FINN AND KATHRYN CRAMER

ATMOSPHÆRA INCOGNITA—NEAL STEPHENSON

GIRL IN WAVE : WAVE IN GIRL—KATHLEEN ANN GOONAN

BY THE TIME WE GET TO ARIZONA—MADELINE ASHBY

THE MAN WHO SOLD THE MOON—CORY DOCTOROW

JOHNNY APPLEDRONE VS. THE FAA—LEE KONSTANTINOU

DEGREES OF FREEDOM—KARL SCHROEDER

TWO SCENARIOS FOR THE FUTURE OF SOLAR ENERGY—ANNALEE NEWITZ

A HOTEL IN ANTARCTICA—GEOFFREY A. LANDIS

PERIAPSIS—JAMES L. CAMBIAS

THE MAN WHO SOLD THE STARS—GREGORY BENFORD

ENTANGLEMENT—VANDANA SINGH

ELEPHANT ANGELS—BRENDA COOPER

COVENANT—ELIZABETH BEAR

QUANTUM TELEPATHY—RUDY RUCKER

TRANSITION GENERATION—DAVID BRIN

THE DAY IT ALL ENDED—CHARLIE JANE ANDERS

TALL TOWER—BRUCE STERLING

SCIENCE AND SCIENCE FICTION: AN INTERVIEW WITH PAUL DAVIES

ABOUT THE EDITORS

EDITED BY KATHRYN CRAMER AND DAVID G. HARTWELL

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

CREDITS

COPYRIGHT

COPYRIGHT NOTICES

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

FOREWORD

Lawrence M. Krauss

SCIENCE FICTION SHARES WITH science a most important driver: a fascination with the possibilities of existence. As a theoretical physicist, my motivation for studying the universe has always been the wonder of what might be possible rather than what is practical. This makes me particularly sympathetic to the challenges facing science fiction writers. After all, perhaps the most significant difference between science and science fiction is that the former explores what is possible in our universe, and the latter what might be possible in any universe.

This is not to minimize the significance of this important distinction. The renowned physicist Richard Feynman once said that “science is imagination in a straitjacket.” It is wonderful to let one’s imagination roam, but forcing our ideas to conform to the evidence of reality, and being willing to throw out ideas, even beautiful ones, if nature turns out not to use them, is hard even for those of us who spend our lives preparing to do just that.

In my own field of cosmology, for example, we have been forced, kicking and screaming, by the data to give up the comforting notion that the energy of empty space had a commonsense value, namely zero, and have instead had to come to grips with the fact that empty space contains the dominant energy in the universe, producing a kind of cosmic antigravity that will determine our ultimate future.

In this regard it is perhaps appropriate to suggest instead that science fiction is the literature where we keep the beautiful ideas and throw out the data . . . namely, where we are free to conjure new realities that conform to our ideas.

So it is that I am often unimpressed when people claim that science fiction anticipates science. It doesn’t. The imagination of the natural world far exceeds that of even the most gifted science fiction writer. The really big advances in science are most often unforeseen, which is one of the things that makes science so fascinating and so much fun to be involved in. These include serendipitous discoveries like the antibiotic capability of penicillin, the weird behavior of the expanding universe I alluded to above, or even the overwhelming social revolution created by the World Wide Web.

When science fiction and science do converge, there is rarely a causal connection, but rather it is generally because creative people can come up with independent but similar solutions to well-known problems. Thus, for example, faced with the possibility that opening someone up to explore inside his or her body might be less desirable than probing metabolic processes from the outside, the writers of Star Trek invented the “tricorder,” whereas in the real world, scientists came up with ultrasound, CAT scans, and MRI machines. The latter were far more difficult to actually make work than the former of course, so it is not surprising that they arose later.

Of course there are periodically examples of science fiction inspiring real-life designers. The original flip cell phone was inspired by Star Trek, and the X-Prize Foundation now has a prize for someone to develop a real-life tricorder. But these are the exception, rather than the rule.

This is what makes the current anthology so intriguing and ambitious. In this collection of stories, science fiction writers, futurists, and technology writers have been challenged to come up with stories on the hairy edge of current reality—exploring possibilities that might actually spur useful collaborations with scientists and engineers to produce new technologies to deal with problems just beyond our current horizon. As Neal Stephenson put it when he founded Project Hieroglyph: the collection should involve a moratorium on “hackers, hyperspace and holocaust.” Namely, it should avoid the classic science fiction hooks: a dystopian future or technology so advanced that the world it describes bears little or no relation to our world.

The stories in this anthology range over a locus of possibilities that take up just where current science and technology hang. I suppose one had to expect at least one story about space travel, that area that engenders such disappointment among those who grew up with the agonizing technological coitus interruptus of the Apollo program. Gregory Benford’s space-based saga may be mere wishful thinking, but a central facet of it revolves around technology that at least some entrepreneurs are taking seriously—mining asteroids for raw materials that might be used both to relieve scarcities here on Earth and to construct facilities in space. I wouldn’t personally invest in this likelihood—I just don’t see a business model that actually works—but if you examine my real-life investments, it is not difficult to distinguish my business acumen from Warren Buffett’s. And whatever one can say about the remarkable waste of resources associated with human space exploration—which gets in the way of doing good science at NASA—it is hard to argue that our future, if there is to be one, will in the long run expand beyond the confines of our planet.

More grounded, if you will forgive the pun, is Neal Stephenson’s piece about building a twenty-kilometer tower on Earth. At first glance it seems to defy reason, but what are the actual limits of civil engineering? The Tower of Babel didn’t work out well for anyone involved, but like the bulk of the Bible, that story was just a fairy tale, and a pretty boring one at that. What if one seriously contemplates such a project?

Are there any laws of physics that really make this impossible? This idea has spawned a collaboration with engineers at Arizona State University. Time will tell if it leaps from a sparkle in Stephenson’s eye to reality. Other stories include subjects at the heart of modern science innovation, from neuroscience and memory storage to 3-D printers. Whatever skepticism one might bring to the likely success of such speculations for productively influencing ongoing scientific or engineering research, the true hallmark of good science fiction is, surprisingly perhaps, not based primarily on the science.

Too often we concentrate on the first word in science fiction and not the second. If a science fiction story is not dramatically compelling, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, for readers to suspend disbelief and immerse themselves in the action. In this sense, nothing distinguishes science fiction from the rest of fiction. All these literary works create a make-believe universe that has to be just real enough to make the dramatic tension that arises between the protagonists both convincing and compelling.

Many of the stories in this collection exemplify precisely this development of dramatic tension that turns potentially pale futuristic ideas into compelling pieces of

fiction. For example, 3-D printing is a new technology that is already inspiring the public’s imagination, from allowing fabrication of intricate mechanical devices in the third world to building human organs cell by cell. Cory Doctorow’s beautiful story “The Man Who Sold the Moon,” however, pushes these ideas one step further by suggesting that 3-D printers could be put on the moon to create building materials that might one day be used by future colonists. What makes the story truly come alive, however, and allows one to suspend disbelief at the remarkable technological hurdles involved, is the deep friendship between three misfits who meet by accident as drug-addled Burning Man partygoers and who overcome personal demons and disease to build lives together.

Similarly, the emerging attempts to inject neuroscience more fully into the legal system, from the search for some form of lie detection that might actually work to serious efforts to anticipate behavior before it happens, are, for many of us, chilling developments. But perhaps nowhere near as chilling as Elizabeth Bear’s “Covenant.” Taking the simple idea that eventually we may be able to alter neurophysiology sufficiently to change character, Bear goes inside the mind of a serial killer and inserts that concept in a gripping cat-and-mouse chase where prey and predator can be confused.

Science fiction has also often been a convenient method of projecting social insights in a way that avoids traditional stereotypes that produce emotional baggage that often otherwise distorts reality. Going back all the way to the nineteenth century, Edward Abbott’s Flatland described a fictitious world of two-dimensional beings, where the highest form of social class, circles, were priests, and the lowest form, lines, were women. Women were dangerous because a line disappears when it is coming toward you and thus could pierce you, so separate entrances were needed for them in every building. In this way Abbott could satirize the Victorian subjugation of women without having to refer to any ongoing political issues.

So too in this collection one finds several stories, notably Madeline Ashby’s “By the Time We Get to Arizona” and Karl Schroeder’s “Degrees of Freedom,” that explore how future advanced technology—in the case of Ashby’s piece it is sensor technology and human-machine interfaces, and in Schroeder’s it is the increasing sophistication of data analysis and retrieval on the Internet—can nevertheless cast new light on current real-world problems. In Ashby’s piece it is the constant fear that many illegal immigrants now feel in the United States about being “outed” and deported in spite of the fact that they may be productive members of our society, and in Schroeder’s it is the time invariant struggle of the individual versus the state—the very thing that Rousseau talked about when he said we are all born free and yet will forever be in chains. But that struggle has taken on a new dimension in the virtual world of the Internet. As online interconnections grow, and the data on everything from our shopping preferences to our network of friends becomes accessible, those who can best utilize this information can best manipulate us.

If it is these sorts of dramas that drive good science fiction, rather than merely the science, one might question whether science fiction can play any role at all in pushing forward progress of science and technology. Here, I defer to my friend and colleague Stephen Hawking, who wrote the foreword for my book The Physics of Star Trek. As he put it: “Science fiction like Star Trek helps inspire the imagination.”

I know very few working scientists who did not enjoy science fiction during their formative years. The question then naturally arises: Which came first? Did a love of science fiction inspire a fascination with science, or did a fascination with things scientific engender an interest in a segment of literature with scientific overtones?

Although a natural question, I would argue, in the spirit of Hawking, that it is largely unimportant. There is little doubt that science fiction as a genre legitimizes the activity—especially among impressionable adolescents—associated with imagining both what is possible in the universe and how to find out. It therefore can help promote a fascination with the poetry of reality while providing an outlet for creative imagining about the world. And that creative imagining is at the heart of the process of science. I would be remiss if I didn’t note that it also provides another important opportunity for young people to grow. It gives them an excuse to read. I suspect that there are many people today who would have been embarrassed to be caught with a book under their arms, unless that book were a science fiction book. The long connection between science fiction and pulp novels legitimized, for a generation, the possibility that reading, thinking, and enjoyment might actually go hand in hand.

Which brings me back to the beginning of this essay. The beauty of science lies for me not merely in its ability to produce fantastic new technologies that transform and can improve the human condition. It is rather in its ability to open our eyes to the endless wonder of the real universe, which continues to surprise us every time we open a new window upon it, even when that window is a literary one. If we ever stop imagining the myriad possibilities of existence, or stop exploring ways to determine whether reality encompasses them, then the human drama will no longer be worth writing about, either in fiction or nonfiction.

PREFACE: INNOVATION STARVATION

Neal Stephenson

MY LIFE SPAN ENCOMPASSES the era when the United States of America was capable of launching human beings into space. Some of my earliest memories are of sitting on a braided rug before a hulking black-and-white television, watching the early Gemini missions. In the summer of 2011, at the age of fifty-one—not even old—I watched on a flatscreen as the last space shuttle lifted off the pad. I have followed the dwindling of the space program with sadness, even bitterness. Where’s my donut-shaped space station? Where’s my ticket to Mars? Until recently, though, I have kept my feelings to myself. Space exploration has always had its detractors. To complain about its demise is to expose oneself to attack from those who have no sympathy that an affluent, middle-aged white American has not lived to see his boyhood fantasies fulfilled.

Still, I worry that our inability to match the achievements of the 1960s space program might be symptomatic of a general failure of our society to get big things done. My parents and grandparents witnessed the creation of the automobile, the airplane, nuclear energy, and the computer, to name only a few. Scientists and engineers who came of age during the first half of the twentieth century could look forward to building things that would solve age-old problems, transform the landscape, build the economy, and provide jobs for the burgeoning middle class that was the basis for our stable democracy.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010 crystallized my feeling that we have lost our ability to get important things done. The OPEC oil shock was in 1973—almost forty years earlier. It was obvious then that it was crazy for the United States to let itself be held economic hostage to the kinds of countries where oil was being produced. It led to Jimmy Carter’s proposal for the development of an enormous synthetic fuels industry on American soil. Whatever one might think of the merits of the Carter presidency or of this particular proposal, it was, at least, a serious effort to come to grips with the problem.

Little has been heard in that vein since. We’ve been talking about wind farms, tidal power, and solar power for decades. Some progress has been made in those areas, but energy is still all about oil. In my city, Seattle, a thirty-five-year-old plan to run a light rail line across Lake Washington is now being blocked by a citizen initiative. Thwarted or endlessly delayed in its efforts to build things, the city plods ahead with a project to paint bicycle lanes on the pavement of thoroughfares.

In early 2011, I participated in a conference called Future Tense, where I lamented the decline of the manned space program, then pivoted to energy, indicating that the real issue isn’t about rockets. It’s our far broader inability as a society to execute on the big stuff. I had, through some kind of blind luck, struck a nerve. The audience at Future Tense was more confident than I that science fiction (SF) had relevance—even u

tility—in addressing the problem. I heard two theories as to why:

1. The Inspiration Theory. SF inspires people to choose science and engineering as careers. This much is undoubtedly true, and somewhat obvious.

2. The Hieroglyph Theory. Good SF supplies a plausible, fully thought-out picture of an alternate reality in which some sort of compelling innovation has taken place. A good SF universe has a coherence and internal logic that makes sense to scientists and engineers. Examples include Isaac Asimov’s robots, Robert Heinlein’s rocket ships, and William Gibson’s cyberspace. As Jim Karkanias of Microsoft Research puts it, such icons serve as hieroglyphs—simple, recognizable symbols on whose significance everyone agrees.

Researchers and engineers have found themselves concentrating on more and more narrowly focused topics as science and technology have become more complex. A large technology company or lab might employ hundreds or thousands of persons, each of whom can address only a thin slice of the overall problem. Communication among them can become a mare’s nest of e-mail threads and PowerPoints. The fondness that many such people have for SF reflects, in part, the usefulness of an overarching narrative that supplies them and their colleagues with a shared vision. Coordinating their efforts through a command-and-control management system is a little like trying to run a modern economy out of a politburo. Letting them work toward an agreed-on goal is something more like a free and largely self-coordinated market of ideas.

SPANNING THE AGES

SF has changed over the span of time I am talking about—from the 1950s (the era of the development of nuclear power, jet airplanes, the space race, and the computer) to now. Speaking broadly, the techno-optimism of the Golden Age of SF has given way to fiction written in a generally darker, more skeptical, and ambiguous tone. I myself have tended to write a lot about hackers—trickster archetypes who exploit the arcane capabilities of complex systems devised by faceless others.

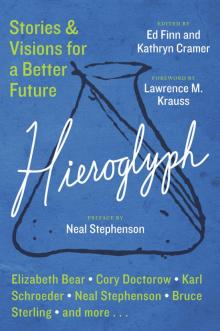

Visions, Ventures, Escape Velocities: A Collection of Space Futures

Visions, Ventures, Escape Velocities: A Collection of Space Futures Hieroglyph

Hieroglyph